Project GO

Tornadoes

Overview

Standards

Background Information

The following information about tornadoes is taken from NOAA’s “Severe Weather 101-Tornado Basics”. This is not nearly the depth of breadth of tornado information, but provides, as the title suggests, the basics. The following information is provided to prepare yourself before teaching about tornadoes. This can also be a resource for students to use when they research tornadoes during Lesson 1. We highly recommend that you look at more than one source for information and knowledge about tornadoes. Tornadoes is also a part of the science curriculum. Refer to science books as an additional resource.

Some of the information below can be used to answer questions for Worksheet 3: Lesson Assessment, for Lesson 1.

What is a tornado?

A tornado is a narrow, violently rotating column of air that extends from the base of a thunderstorm to the ground. Because wind is invisible, it is hard to see a tornado unless it forms a condensation funnel made up of water droplets, dust and debris. Tornadoes are the most violent of all atmospheric storms.

What are the wind speeds in a tornado?

We're not really sure what the highest wind speed might be inside a tornado, since strong and violent tornadoes destroy weather instruments. We really only have measurements of the winds inside weaker tornadoes. Mobile Doppler radars can measure wind speeds in a tornado above ground level, and the strongest was 318 mph measured on May 3, 1999 near Bridge Creek/Moore, Oklahoma.

How fast do tornadoes move?

We don't have detailed statistics about this. Movement can range from almost stationary to more than 60 mph. A typical tornado travels at around 10–20 miles per hour.

Where do tornadoes come from?

Tornadoes come from the energy released in a thunderstorm. As powerful as they are, tornadoes account for only a tiny fraction of the energy in a thunderstorm. What makes them dangerous is that their energy is concentrated in a small area, perhaps only a hundred yards across. Not all tornadoes are the same, of course, and science does not yet completely understand how part of a thunderstorm's energy sometimes gets focused into something as small as a tornado.

Where do tornadoes occur?

Whenever and wherever conditions are right, tornadoes are possible. In the U.S. they are most common in the central plains of North America, east of the Rocky Mountains and west of the Appalachian Mountains. They occur mostly during the spring and summer; the tornado season comes early in the south and later in the north because spring comes later in the year as one moves northward. They usually occur during the late afternoon and early evening. However, they have been known to occur in every state in the United States, on any day of the year, and at any hour. They also occur in many other parts of the world, including Australia, Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America. Even New Zealand reports about 20 tornadoes each year. Two of the highest concentrations of tornadoes outside the U.S. are Argentina and Bangladesh.

How many tornadoes occur in the U.S. each year?

About 1,200 tornadoes hit the U.S. yearly. Since official tornado records only date back to 1950, we do not know the actual average number of tornadoes that occur each year. Plus, tornado spotting and reporting methods have changed a lot over the last several decades.

Where is tornado alley?

Tornado Alley is a nickname invented by the media for a broad area of relatively high tornado occurrence in the central U.S. Various Tornado Alley maps look different because tornado occurrence can be measured many ways: by all tornadoes, tornado county-segments, strong and violent tornadoes only, and databases with different time periods. Please remember, violent or killer tornadoes do happen outside “Tornado Alley” every year.

http://ichef-1.bbci.co.uk/news/624/media/images/67729000/gif/_67729031_number_of_tornadoes_624.gif

When are tornadoes most likely to occur?

Tornado season usually refers to the time of year the U.S. sees the most tornadoes. The peak “tornado season” for the Southern Plains is during May into early June. On the Gulf coast, it is earlier during the spring. In the northern plains and upper Midwest, tornado season is in June or July. But, remember, tornadoes can happen at any time of year. Tornadoes can also happen at any time of day or night, but most tornadoes occur between 4–9 p.m.

What is the difference between a Tornado WATCH and a Tornado WARNING?

A Tornado WATCH is issued by the NOAA Storm Prediction Center1 meteorologists who watch the weather 24/7 across the entire U.S. for weather conditions that are favorable for tornadoes. A watch can cover parts of a state or several states. Watch and prepare for severe weather and stay tuned to NOAA Weather Radio to know when warnings are issued.

A Tornado WARNING is issued by your local NOAA National Weather Service Forecast Office2 meteorologists who watch the weather 24/7 over a designated area. This means a tornado has been reported by spotters or indicated by radar and there is a serious threat to life and property to those in the path of the tornado. ACT now to find safe shelter! A warning can cover parts of counties or several counties in the path of danger.

Watch this Youtube video3 for a great explanation!

How is tornado strength rated?

The most common and practical way to determine the strength of a tornado is to look at the damage it caused. From the damage, we can estimate the wind speeds. An “Enhanced Fujita Scale”4 was implemented by the National Weather Service in 2007 to rate tornadoes in a more consistent and accurate manner. The EF- Scale takes into account more variables than the original Fujita Scale (F-Scale) when assigning a wind speed rating to a tornado, incorporating 28 damage indicators such as building type, structures and trees. For each damage indicator, there are 8 degrees of damage ranging from the beginning of visible damage to complete destruction of the damage indicator. The original F-scale did not take these details into account. The original F- Scale historical data base will not change. An F5 tornado rated years ago is still an F5, but the wind speed associated with the tornado may have been somewhat less than previously estimated. A correlation between the original F-Scale and the EF-Scale has been developed. This makes it possible to express ratings in terms of one scale to the other, preserving the historical database.

https://www.almanac.com/content/how-measure-tornadoes-ef-scale

How do tornadoes form?

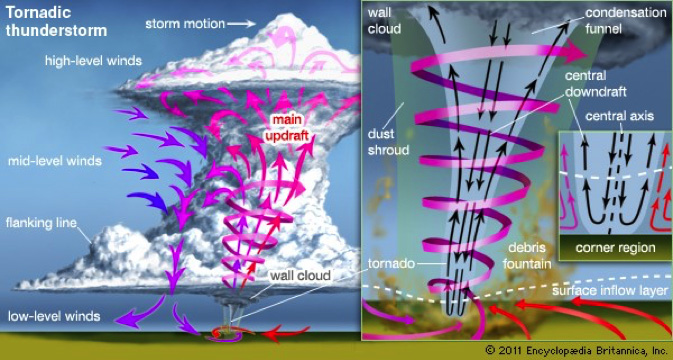

The truth is that we don't fully understand. The most destructive and deadly tornadoes occur from supercells, which are rotating thunderstorms with a well-defined radar circulation called a mesocyclone. (Supercells can also produce damaging hail, severe non-tornadic winds, unusually frequent lightning, and flash floods.) Tornado formation is believed to be dictated mainly by things which happen on the storm scale, in and around the mesocyclone. Recent theories and results from the VORTEX25 program suggest that once a mesocyclone is underway, tornado development is related to the temperature differences across the edge of downdraft air wrapping around the mesocyclone. Mathematical modeling studies of tornado formation also indicate that it can happen without such temperature patterns; and in fact, very little temperature variation was observed near some of the most destructive tornadoes in history on 3 May 19996. We still have lots of work to do.

What do storm spotters look for when trying to identify a tornado or a dangerous storm?

Inflow bands are ragged bands of low cumulus clouds extending from the main storm tower usually to the southeast or south. The presence of inflow bands suggests that the storm is gathering low-level air from several miles away. If the inflow bands have a spiraling nature to them, it suggests the presence of rotation.

The beaver's tail is a smooth, flat cloud band extending from the eastern edge of the rain-free base to the east or northeast. It usually skirts around the southern edge of the precipitation area. It also suggests the presence of rotation.

A wall cloud is an isolated cloud lowering attached to the rain-free base of the thunderstorm. The wall cloud is usually to the rear of the visible precipitation area.

A wall cloud that may produce a tornado usually exists for 10–20 minutes before a tornado appears. A wall cloud may also persistently rotate (often visibly), have strong surface winds flowing into it, and may have rapid vertical motion indicated by small cloud elements quickly rising into the rain-free base.

As the storm intensifies, the updraft draws in low-level air from several miles around. Some low-level air is pulled into the updraft from the rain area. This rain-cooled air is very humid; the moisture in the rain-cooled air quickly condenses below the rain-free base to form the wall cloud.

The rear flank downdraft/ (RFD) is a downward rush of air on the back side of the storm that descends along with the tornado. The RFD looks like a “clear slot” or “bright slot” just to the rear (southwest) of the wall cloud. It can also look like curtains of rain wrapping around the cloud base circulation. The RFD causes gusty surface winds that occasionally have embedded downbursts. The rear flank downdraft is the motion in the storm that causes the hook echo feature on radar.

A condensation funnel is made up of water droplets and extends downward from the base of the thunderstorm. If it is in contact with the ground it is a tornado; otherwise it is a funnel cloud. Dust and debris beneath the condensation funnel confirm a tornado's presence.

The photos below provide different visuals that explain how tornadoes are formed, the strength of tornadoes based upon the Fujita Scale, and a representation of where tornadoes occur.

http://www.britannica.com/science/tornado/images-videos